A motif is a recurring element - a pattern that is found more often than would occur by chance. They are essential in all ordered systems, from genetic networks to the patterns of social interaction. Today we’re going to talk about their role in music while we reviewing the ways that you can teach robots to write songs.

For the purposes of this post, we’re going to understand a musical work as a simple sequence of notes. How we move from one note to the next is what produces this emergent “musicality”. The foundation of most robot-composers like Emily Howell are markov chains. For more information on what those are, and to see some of the foundational code that made this post possible, read Victor Powell, he is master of us all. Markov chains can be used to create biased random walks between notes which, absent of any grand form, can still produce musicality.

The network bellow shows one such markov chain that hops around the pentatonic scale. This scale is nice for generating random music because it lacks any dissonant intervals.

This biased random walk reveals that certain notes are favored, a phenomenon emerging from the probabilty weights between the jumps. Play with the speed and unmute it to hear this network performed. Note, I added some random rhythms on top just to keep the notes interesting (quarter and eight notes, 50% probability each)

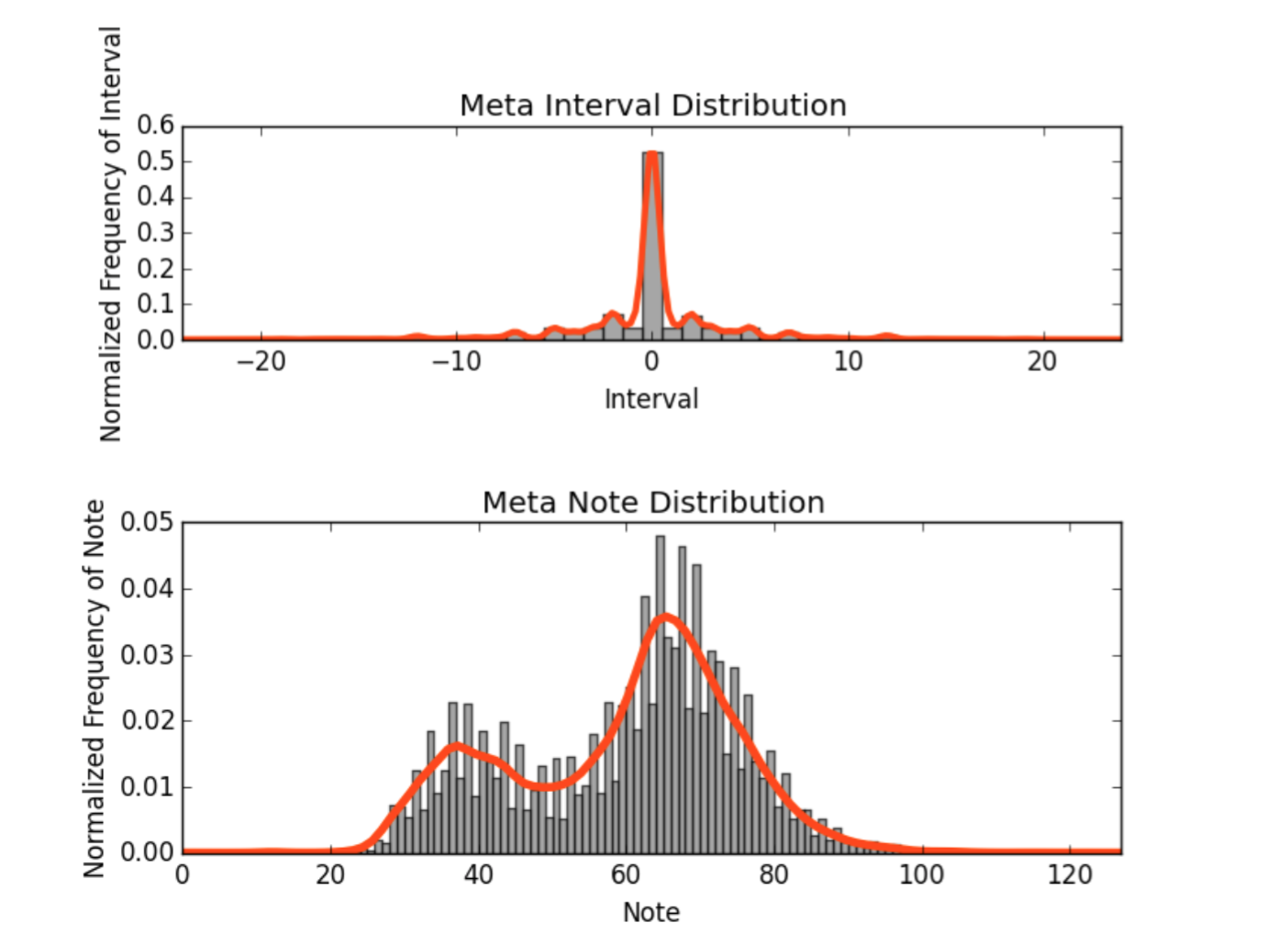

So the figure above showed that a biased random network can generate the semblance of musicality. However, the weights between the nodes (or the probability of each transition) are super important in making your robo-music not sound like utter garbage. In order to “discover” the appropriate weights, I told my computer to scrape a bunch of songs from the web, analyze them, and tell me how we transition from one note to the next. It was complicated. Below we see the note and interval distributions from ~2000 pop songs.

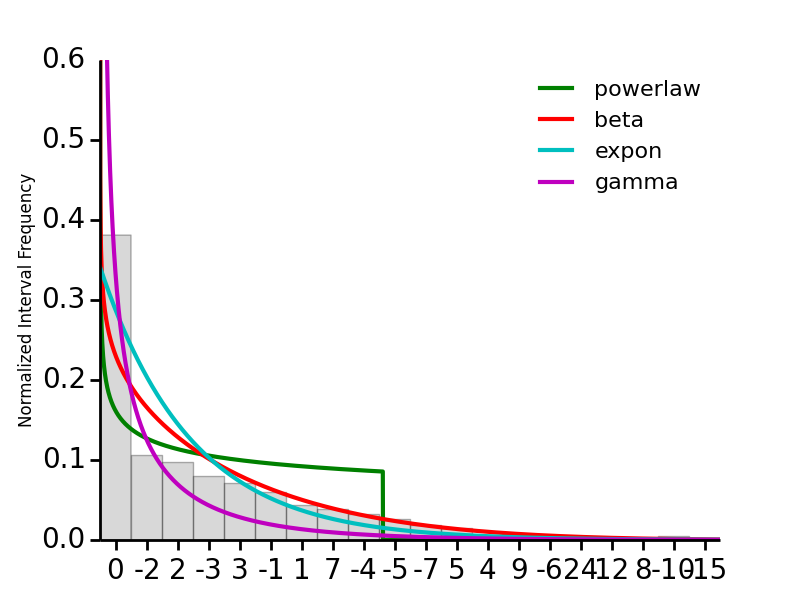

These are produced from what might come from a summing up a bunch of histograms like the animated one above for a whole slew of pop songs. The interval diagram (the distance from one note to the next) shows that clearly not moving at all (staying on the same note) is the most favored transition. This is emphasized by looking at our case-study song, Bad romance by Lady Gaga, and fitting a few different distributions to show how we move throughout this song.

Say what you will, but i’m calling that as an exponential distribution. This fact can be used to inform our procedural music model later on.

There is an important element that these simple random walks can’t quite capture though : the motif. We can think of motifs in music as hooks. The melody you’ll hum when you think of the song. Take Bad Romance by Lady Gaga, the hook is unforgetable. However let’s try to generate it from a markov chain:

Using all of my stats power, I can say (not counting rhythm) that even with the optimal weights we’re still looking at ~3% chance that the hook will be generated if you start on the tonic. Not so hot. As a result we need to generate musicality not just from the probabilities of note transitions, but also the recurrence of grander symmetry.

Real full-blown actual real life scientists have studied this problem and used fancy math to analyze the frequency of recurrent patterns. For me I’m just gonna prospect the hooks.

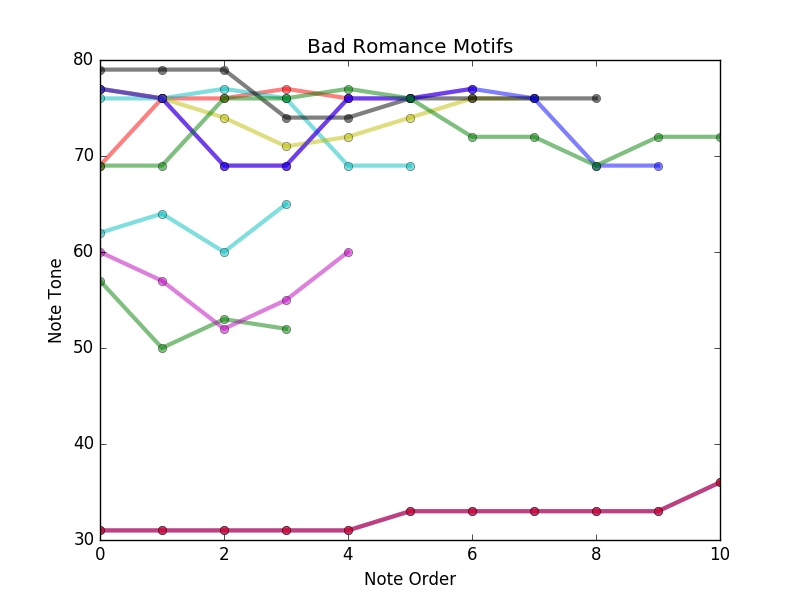

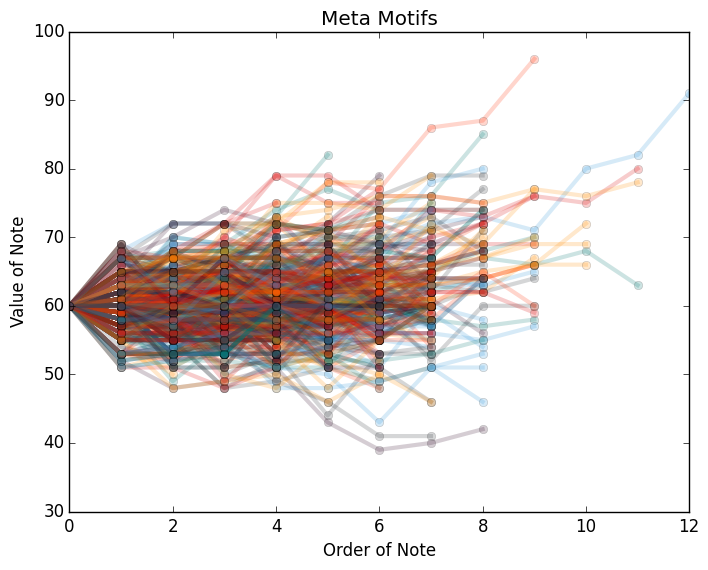

Going back to our data and using some computer science shenanigans we can find which patterns are most common, as is demonstrated by the graph below (see github for how this was done):

Note the presence of the RA-AH-GA-GA-AH-AH echoed in some of the prospected motifs (hint 62 is middle - C). Clearly some imperfect musical fragments were also recovered, but overall we see that it not just about probabilities between notes, there are also bigger patterns that recur.

Prospecting the most common motif from all 5000 songs reveals what approximates to be a zero-mean Markovian process for each of the hooks if you center them at the same starting pitch.

So how do we know that any of this actually makes something sound musical? Well, we need to give a robot these rules that we found to be common in other peoples music, and ask it to use them to generate new music. I did just that when I wrote an evolutionary algorithm bringing together both the ideas of Markovian interactions and motif recurrence to turn this:

into this:

Not perfect, but you can hear the elements coming together.

The musical markov chain visualizations were done by adapting this, with help from midi.js.

The web-scrapping took midi files from various repositories across the web and parsed them with Beautiful Soup and python midi libraries. Code and sample midi files available here.

I used matlab to write the evolutionary algorithm to combine the themes and write the novel music (I almost never use matlab but I had some code I previously wrote that made it easy). Not available on github, but just email me if you have questions.